a brief history of mobulid fisheries

In general, the flesh of all sharks and rays is not considered as good to eat as that of bony fishes, such as cod, herring, tuna, groupers, billfishes, etc. As a result, commercial and artisanal fishermen have mostly avoided fishing for these cartilaginous animals in the past centuries, instead concentrating their efforts to fish for the ‘tastiest’ species in our oceans. However, as stocks of our sea’s most plentiful and desirable species have become dramatically depleted, fishermen and nations have turned from the occasional artisanal consumption of mobulids for food, to commercial fisheries for their flesh and to sell their dried branchial gill filaments (known as 'gill plates') as an increasingly sought after ingredient in some Asian medicines. It is often a sad fact of human nature that the more endangered a wild animal becomes, the greater our desire to possess or consume it. Diminishing stocks drive a lucrative trade (often illegal) to hunt down, trade in, and consume the dwindling populations of these endangered species.

An image from an issue of National Geographic Magazine in 1919. The caption describes the enormous effort that went into landing this manta. Along with their undesirable taste, the level of effort required to catch and bring a manta to port, and the risks associated with doing so, meant manta and devil rays were largely avoided by fisheries.

The Sea of Cortez - One of the First Targeted Mobulid Fisheries

Among the first countries to commercially fish their manta population was Mexico, when in the early 1980’s fishermen in the Sea of Cortez switched from subsistence and bycatch fishing of the locally abundant oceanic manta and devil ray species to a directed target fishery. Using harpoons to impale the surface feeding animals, and gill nets to entangle and drown them, the rays were easy targets and their numbers soon began to plummet. Only the choicest flesh was sold for consumption, while the remainder was often used as bait in lobster pots, or simply discarded. Within just a decade the manta ray population within the Sea of Cortez was virtually wiped out and the fishery collapsed. It was not until 2007 that the Mexican Government finally passed legislation protecting the manta and mobula rays in Mexican waters, but by then the damage had already been done. Even today, after over a decades since the fisheries collapsed, virtually no mantas are recorded in this area and those that are still fall victim to illegal fishing, or bycatch.

Many other countries have also targeted their manta and devil ray populations with similar results, switching from a local artisanal fishery to a commercial export fishery wherever a market for their products can be found. The Philippines, Indonesia, Mozambique, Madagascar, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Brazil, Peru, and Tanzania have all followed Mexico’s lead, with similar trends of population declines reported in many of these countries where data exists. Yet out of all these countries, only in Indonesia, Peru and the Philippines are there now national laws in place to protect these vulnerable species.

to kill for a gill

So why the sudden change of fortune for the world's manta and devil rays? The underlying answer to this question is not a new one. In fact, it’s a depressing repetition played out in our oceans and throughout our planet on a regular basis. The difference this time is that the latest targets are the mobulids - the newest commodity in the often senseless and environmentally destructive Asian Medicinal Trade.

In recent decades, a new market for mobulid gill plates has developed for their use in a medicinal tonic. Gill plates, or branchial filaments, are thin cartilage filaments that enable manta and devil rays to filter zooplankton out of the water column. Retailers claim that just as mobulids use gill plates to filter plankton from the water, they can aid in the detoxification and purification of the consumer by filtering disease and toxins from the body. However, there is no scientific evidence to support these claims. Worse still is that gill plates are not truly a Traditional Medicine - the demand has arisen due to product marketing by retailers, who have falsely ‘revived’ a remedy that never existed in the traditional literature.

Fisheries targeting mobulid rays for their highly-prized gills have had a devastating impact on populations, resulting in mantas being listed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species.

What has been done to combat the trade?

In March 2013, following considerable work and pressure from the Manta Trust and collaborating NGOs, mantas were listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). This legislation means that countries must prove that any international trade in manta gill plates is sustainable and non-detrimental to the survival of the species; essentially an impossibility due to their conservative life-history traits. In 2016 similar success at CITES was achieved for all species of devil ray too. In addition to CITES, all mobulid species are now also listed on Appendix I and II of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS).

These are enormous steps forward in reducing the viability of the gill plate trade. But of course, laws and regulations mean nothing if countries do not take action to enforce it. An important aspect of the work we do through our Global Mobulid Conservation Programme revolves around providing the tools and training governments need to apply CITES and CMS legislation in the real world.

Members of the Manta Trust, alongside partners from WildAid, celebrating in March 2013 - when mantas became listed on Appendix II of CITES.

the threat from bycatch

Despite enhanced protection against the gill plate trade, mantas are still being killed in their thousands, and devil rays in their tens of thousands, as victims of bycatch in high seas fisheries.

The term “bycatch” is used to describe fish, or other animals, which are caught unintentionally in a fishery. Few fishing techniques can target a single species, and some of the most destructive forms of fishing including drift nets (now illegal in international waters and within many nation’s territorial waters), long-lining and gill-netting, are responsible for much of the world's bycatch.

These destructive techniques indiscriminately catch and kill huge numbers of some of our ocean’s most endangered species; from dolphins and whales, to sea turtles, albatrosses and sharks, as well as the manta rays. The oceanic manta ray (Mobula birostris), and many of the devil ray species are especially vulnerable to these oceanic fisheries, falling victim to bycatch as they migrate vast distances across the tropical and sub-tropical oceans of the world.

Accurate data on the number of mobulids landed as bycatch is hard to come by. This is an important challenge which we seek to address as a charity, as informed management decisions cannot be made without the numbers to quantify the threat, and the need for effective solutions.

A manta killed in nets in Grenada, Caribbean.

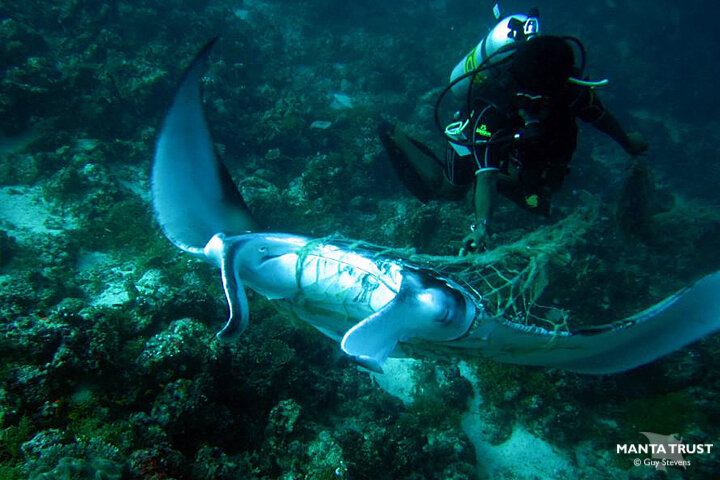

Divers with knives / line-cutters are sometimes able to help entangled animals - but these are the lucky few.

In addition to threats from high-seas fisheries, entanglement poses a particular issue for mobulid rays. As manta rays cannot swim backwards and have to continuously swim forward in order to move water over their gills, they often get caught and trapped in fishing and mooring lines. As the line catches onto their bodies, gill slits, mouths or cephalic fins, they perform backward rolls and turns in an attempt to free themselves. Unfortunately, this often entangles them further. If they are “lucky”, the line will break free and trail out behind the manta, cutting like cheese wire through skin, muscles, and eventually into their vital organs, often causing permanent damage and sometimes death.

Every year divers and snorkelers observe many mobulid rays still entangled in fishing line, or discarded and broken fishing nets which drift around the world’s oceans “ghost fishing” in countless numbers. The animals which do encounter divers or snorkelers are the lucky few because they are often able to be cut free. However, the unfortunate majority of entangled mantas are destined for a slow and painful death. In countries such as South Africa, manta and devil rays also fall victim to entanglement in shark-nets used to try and reduce shark attacks on humans at some of the busiest recreational beaches.