INTRODUCTION TO TELEMETRY

Animal telemetry is the science of gathering information on the movement and behaviour of organisms using animal-borne sensors, or tags, and is a critical tool for researchers and conservationists. Telemetry studies have been used on a vast range of species from tiny insects to mountain lions, to albatrosses, great white sharks, and many more in between. Although ocean based tracking brings with it new challenges, the methods have still been used on an extensive range of species, as seen in the figure below.

Satellite telemetry (tagging) has been used on dozens of marine species. This map highlights the diversity of species tagged in just one study; the Tagging of Pelagic Predators (TOPP) programme. Figure from Block et al., 2011.

Telemetry studies have provided vital insight into the movement and behavioural ecology of manta and devil rays. This knowledge has been used to design effective conservation strategies for these vulnerable animals where these studies have taken place. On this webpage we explore some of the important research questions that these tools can help to answer, look at the types of tags and tracking methods widely used, examine how these activities affect mobulid rays, provide details of some fascinating tagging studies, and detail the conservation outcomes these studies have helped to achieve.

TAGGING AND TRACKING MOBULIDS

Oceanic manta ray (Mobula birostris) with a suction cup Crittercam in Mexico.

Manta and devil rays often undertake seasonal migrations, travelling tens, hundreds, and sometimes thousands of kilometres. This means that their habitat can encompass large areas, sometimes crossing national boundaries, where conservation management is often more challenging. Therefore, to effectively protect these animals, we must first understand what habitats they are using, when they are there, and what they are doing within it.

Photo identification (photo-ID) is one of the primary research methods favoured by Manta Trust scientists around the world and, over the last 15 years, it has provided great insight into the movements, size, and demographics of manta ray populations globally. It is a cheap and non-invasive data-collection technique that both trained researchers and members of the public can use. However, it alone cannot tell us everything that we need to know to adequately protect manta rays and their relatives around the world. Learn more about photo-ID and how you can contribute to our citizen science programme, IDtheManta.

A satellite tag deployed on an oceanic manta ray (Mobula birostris) in Mexico.

One of the limitations of photo-ID research is that images can only be collected in locations (and at depths) that scuba divers and snorkellers can access; primarily restricting data collection to shallow reef systems. This means we have learnt a lot more about the spatial and behavioural ecology of the reef manta ray than their larger cousins, which live a more oceanic lifestyle. However, as this recent tagging study led by Initiative Manta En Nouvelle-Caledonie demonstrates, even with all the photo-ID data we have collected, there is still much we can learn about reef manta rays using other research methods. Photo-ID is further limited because most of the data is primarily collected from only a few aggregation sites where researchers know the rays regularly frequent to feed or clean, often for just a few minutes or hours at a time. Therefore, once the rays leave these sites, we have no idea where they are going, or what they are doing; knowledge which is critical if we are to effectively protect these species.

The Manta Trust utilises a wide range of research methods to gather knowledge on mobulid rays globally, which we then use to make informed management recommendations to governments and other stakeholders. These methods often include tagging studies. However, as tagging is an invasive technique, we only use it when it is required to fill vital knowledge gaps.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Click on the questions below to see our answers.

+ Does tagging harm the manta?

Due to the nature of the tag being an inserted dart, tagging is considered invasive. However, if done correctly, by a trained expert, tagging does not cause the manta ray any serious or long-term harm. A tag is inserted in the fold between a manta’s pectoral fin and its body cavity, where it will not damage any internal organs, and it will not get shaken about by the manta’s pectoral fins as they swim.

Watch this video of oceanic manta tagging from Mexico.

+ Does tagging hurt the manta?

It is impossible for us to really know what a manta feels when it is tagged, but we imagine it feels something like a bee sting, or an ear piercing; a short, sharp pain that passes quickly. Every manta reacts different when a tag is first attached, some barely flinch, whilst others dart off quickly. Reef manta rays tend to react more to tagging than oceanic manta rays, which often appear unfazed by the experience.

Watch this video of oceanic manta tagging from Mexico.

+ Does tagging scare manta rays away?

All our tagging studies data shows that manta rays are not deterred from returning to the location where they were tagged (see 'Learn More About Tagging' section below). In fact, researchers often see tagged manta rays return on the same day, reapproaching the same diver who tagged them minutes or hours after being tagged. Furthermore, long-term visitation patterns to the site where the individual was tagged do not change because of the tagging.

Watch this video of oceanic manta tagging from Mexico.

+ Can you track manta rays in real time with tags?

Currently, the only way to do this is from a boat immediately after tagging a manta with an active ‘pinger’ acoustic tag, using a directional hydrophone as described above in the ‘Types of Tags and Tracking’ section. This is a very labour-intensive tracking technique that can only be done for a short period of time. The technology does not exist to remotely track manta rays in real time. Read the section on 'Types of Tags and Trackers' below for more details on how they work.

+ How many manta rays do you need to tag?

This depends on the research question. However, most studies require at least half a dozen individuals to produce meaningful results, and ideally many more. As tagging equipment is very expensive, studies can often only afford 5-15 tags at a time.

+ Manta rays are protected in many countries, so why do they need to be tagged there?

There are several reasons why it is still critical to conduct tagging studies with manta rays in countries where they already have national protection. Some examples of these are:

- To ensure that conservation measures in place are effective and sufficient. As Case Study Three (below) demonstrates, tagging data can help to direct management efforts to ensure that manta hunting does not continue under the radar. It is also important to assess whether other activities that are still permitted are unintentionally harming manta rays, and therefore need managing. For example, expanding tourism, coastal development or the incidental catch (bycatch) of manta rays by fisheries targeting other species.

- To find out if manta rays are travelling into unprotected waters. We know that manta ray habitat can encompass large areas, sometimes crossing national boundaries. So, tagging manta rays within the safeguarded waters of one country can help us to find out if they are travelling into neighbouring waters where they may still be under threat from target fisheries. See Case Study 2 below for a specific example.

- To provide information that can help to drive protective measures in other regions of the world. Gathering data on manta ray movement and behaviour in areas where they are well protected, can help us to learn more about these species at a baseline level (Case Studies 1 & 4 below).

- To learn how anthropogenic threats unimpeded by protective legislation, such as rising sea temperatures or marine pollution, are impacting manta ray populations. Case Study Three (below) is also a great example of this.

Learn more about Tagging

Webinar with Dr. Mark Erdmann of Conservation International about tagging and its uses as a research tool.

Clip of researcher tagging oceanic manta rays (Mobula birostris) in Mexico.

Studies in the Maldives

In the Maldives between 2005 and 2019, 76 individuals (1.5% of the known population) were part of research studies involving either acoustic tags (n= 16 events), a biopsy (n=50 events), a crittercam deployment (n=10 events) or a combination of a biopsy and crittercam deployment on the same day (n=2). Two individuals were included in multiple studies on separate days; therefore, sightings data for these individuals was analysed before and after each of their research days (total of 76 individuals and 78 events).

Ninety-six per cent (n=73) of individuals researched (n=76) have been resighted since being included as part of a research group. In comparison, 76% (n=3,748) of the manta rays photographed in the Maldives (n=4,941) have been recorded more than once. See Figure 1 below for further information on the duration of time between re-sightings of individuals after research events.

Figure 1: Percentage of reef manta rays re-sighted in the Maldives, post-involvement in different research studies by duration of time between re-sightings (n= 50 biopsies, 16 acoustic tags, 10 crittercam deployments, 2 biopsies and crittercam deployments, 4941 initial photo-ID captures). Ninety-six per cent of research events (n=75) resulted in a resighting post biopsy, tagging or crittercam deployment. Seventy-six percent (n=3748) of all individuals photographed (n=4941) in the Maldives have been re-sighted at least once.

Although there is variation between individuals, the vast majority have been resighted in similar frequency after (green dots in Figure 2) a research event as before (blue dots in Figure 2), clearly indicating no long term impact of such research techniques on sightings.

Figure 2: Sightings of individual reef manta rays in the Maldives pre- and post- inclusion in invasive research activities (biopsy, acoustic tag, crittercam, or crittercam and biopsy). Seventy-six individuals (labelled on the Y-axis) were targeted during seventy-eight research events; the day of which has been designated by a pink dot on the timeline. *Note: the end date signifies the end of the 2019 study year. The year of research determined the possible time for sightings before and after the research event.

Laamu Atoll biopsies

A total of 10 biopsies were collected from reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) at Hithadhoo Corner in Laamu Atoll, Maldives between the 10th of August 2016 and the 11th of September 2016. The average residency index (RI) for each manta biopsied was calculated before (0.0294, SD= 0.330) and after (0.0260, SD=0.330) the period where biopsies were collected. A paired t-test showed no significant difference in the residency of individuals included in the study before and after the biopsies [t(9) = 0.216, p = 0.8342]. The mean change in RI was -0.0025 (SD=0.04) for biopsied individuals, whereas the mean change for non-biopsied individuals was -0.0035 (SD=0.02). A Welch two samples t-test showed there was no statistically significant change [t(9.70) = -0.0859, p = 0.933] in residency between the biopsied and non-biopsied manta rays, pre-and post-sampling. Box plots were used to visually compare the differences between biopsied and non-biopsied individuals (Fig. 3). These residency indices were calculated for Hithadhoo Corner sightings between 1st July 2014 and 31st December 2018.

Table 1: Residency Index (RI) and change in RI of reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) at Hithadhoo Corner, Laamu Atoll, Maldives before and after biopsy sampling. Individuals are grouped by whether a biopsy was conducted on the individual between the 10th of August 2016 and the 11th of September 2016.

Figure 3: A box plot shows the changes in the residency index for pre-and post-sampling periods of biopsied and non-biopsied populations of reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) at Hithadhoo Corner, Laamu Atoll, Maldives. Plotted points represent individual manta rays identified at Hithadhoo Corner as of August 2016. A t-test revealed no statistically significant difference in the residency index change of biopsied and non-biopsied manta rays, t(9.70) = -0.0859, p = 0.933.

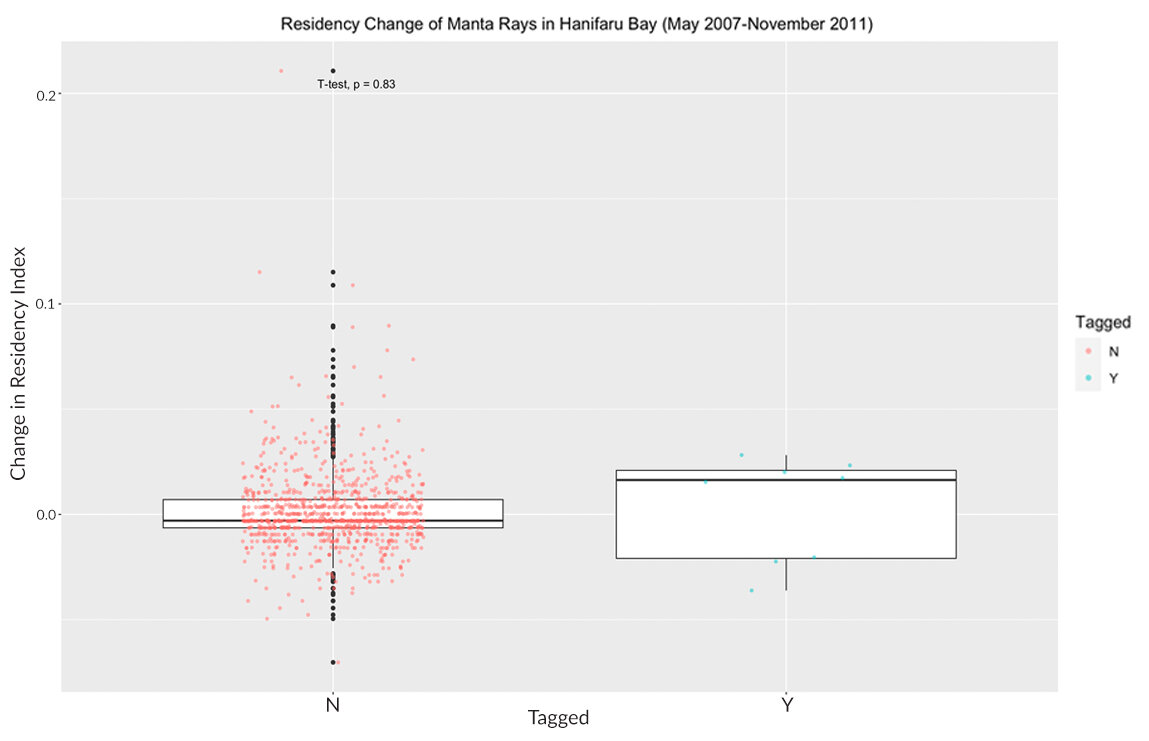

Hanifaru Bay acoustic tagging

Between the 12th of September 2009 and the 29th of September 2009, a total of eight reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) were outfitted with acoustic tags in Hanifaru Bay, Baa Atoll, Maldives. The average residency index (RI) for each manta outfitted with an acoustic tag was calculated before (0.002, SD= 0.002) and after (0.005, SD=0.004) the period where tags were deployed. A paired two samples t-test showed no significant difference in residency between before and after the event [t(7) = -1.637, p = 0.1456]. The mean change in RI was 0.003 (SD=0.004) for tagged individuals, whereas the mean change for non-tagged individuals was 0.001 (SD=0.02). A Welch two samples t-test showed there was no statistically significant change [t(7.06) = -0.226, p = 0.828] in residency between the tagged and non-tagged manta rays, pre-and post-tagging. Box plots were used to visually compare the differences between tagged and non-tagged individuals (Fig. 4). Residency indices were calculated for all individuals identified in Hanifaru Bay prior to the tagging period through November 2011.

Table 2: Residency Index (RI) and change in RI of reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) in Hanifaru Bay, Baa Atoll, Maldives pre-and-post-tagging. Individuals are grouped by whether they were outfitted with a tag between the 12th of September 2009 and the 29th of September 2009.

Figure 4: A box plot shows the changes in the residency index for tagged and non-tagged reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) in Hanifaru Bay, Baa Atoll, Maldives after a tagging period in 2009. Plotted points represent individual manta rays identified in Hanifaru Bay as of the start of the tagging period in September 2009. A t-test revealed no statistically significant difference in the residency index change of tagged and non-tagged manta ray (7.06) = -0.226, p = 0.828.

TAGGING IN THE SCIENTIFIC LITERATURE

Interactive map of published scientific papers on manta and devil rays which utilised acoustic or satellite tracking (Click on the points to access the associated paper).

Within the map are links to papers published on mobulid tagging studies to date, with a few specific examples that demonstrate how well executed tagging research can have a positive impact for manta rays outlined below.

Case Study 1

A recent study in the Seychelles on the reef manta ray population using satellite telemetry identified high levels of site fidelity around D’Arros. The results of this tagging work directly helped inform the creation of the D'Arros Marine Protected Area. The tagging helped to show that the mantas spent a lot of their time around the shallow reef systems, which needed greater protections.

Case Study 2

Spatial ecology and conservation of Manta birostris in the Indo-Pacific: In the absence of ecological data, population declines in oceanic manta rays have been addressed primarily with international-scale management and conservation efforts. However, this recent study used satellite tagging in combination with genetic research to demonstrate that regional approaches to oceanic manta conservation could prove more effective.

Case Study 3

Movement patterns and habitat use of juvenile reef manta rays in a nursery area of Raja Ampat’s Wayag Lagoon: In the six years prior to this project, conservation management of reef manta rays in Indonesia had shown considerable advances, but still little was known about new-born and juvenile manta rays in the region. This tagging study identified Wayag Lagoon in northwest Raja Ampat as a primary nursery and pupping ground for reef manta rays, highlighting the urgent need to limit potentially harmful boating activities inside the lagoon.

In 2014, Indonesia created the world’s largest manta sanctuary, but was only actively enforcing this protection in manta tourism areas. This satellite tagging study (and other unpublished studies in the region) showed conclusively that manta rays from tourism areas were moving through areas known to be manta hunting regions, which convinced the Indonesian government to pursue enforcement in these hunting regions too.

Case Study 4

Satellite tracking of reef manta rays in Sudan confirmed the importance of the Dungonab Bay and Mukkawar Island National Park as an important foraging habitat for this species. This additional weight for supporting the protection of the area is important when considering recent plans for a large-scale island development project including skyscrapers, international airport and extensive dredging activity.